Biliary anatomy and physiology

What is bile?

Bile is a physiological solution produced and secreted by the liver. It's Main function is emulsification of fat.

bile consists of:

- Water (acting as a solvent for all the following)

- Cholesterol

- Conjugated bilirubin

- Bile salts

- Phospholipids

- Electrolytes

Bile travels through the liver in a series of ducts, eventually exiting through the hepatic ducts.

- The right hepatic duct drains bile from the liver's right functional lobe, while the left hepatic duct drains bile from the liver's left functional lobe.

Function of bile:

Fat emulsification

- Bile salts are amphipathic (a molecule with hydrophilic (water attracting) and hydrophobic (water repelling) parts).

- The hydrophobic part binds to lipids, while the hydrophilic part will surround the lipid attracting water and dispersing other fat molecules.

- This stop the fat molecules from reaggregating keeping them separate.

- Bile salts also allow fat to be transported as micelles

- Micelles are larger molecules made up of phospholipid tails, arranged in a fashion to have a hydrophobic core and a hydrophilic outside.

- This arrangement increases the surface area of lipids allowing easier digestion with lipase.

- Micelles are broken down by lipase, releasing fatty acids and monoglycerides in the ileum. Those can diffuse into epithelial cells of the gut to be absorbed

Eliminate waste products

- Cholesterol is eliminated through excretion as bile acid. This allows cholesterol homeostasis.

- Bilirubin is a waste product of the breakdown of RBCs. It is excreted into bile and eventually forms the dark pigment in faeces.

Bilirubin metabolism: from RBC to Bilirubin:

- Red blood cells break down in the spleen/intravascularly after they have completed their normal lifecycle.

- Conjugated bilirubin formed as above will undergo multiple reactions until it gets reduced into urobilinogen (lipid soluble, colourless).

- This will undergo further reactions under effect from gut bacteria to form stercobilin. This gives stool it's brown colour.

Red blood cell haemolysis

Diagram showing the breakdown of haemoglobin to biliverdin

Biliverdin

Biliverdin (green in colour) will be reduced by biliverdin reductase into unconjugated billirubin.

Diagram showing the reactions to form conjugated billirubin

Bilirubin conjugation and excretion

Diagram showing excretion of bilirubin

Summary of Bilirubin metabolism

biliverdin

unconjugated bilirubin

conjugated bilirubin

urobilinogen

excreted via urine and/or faeces

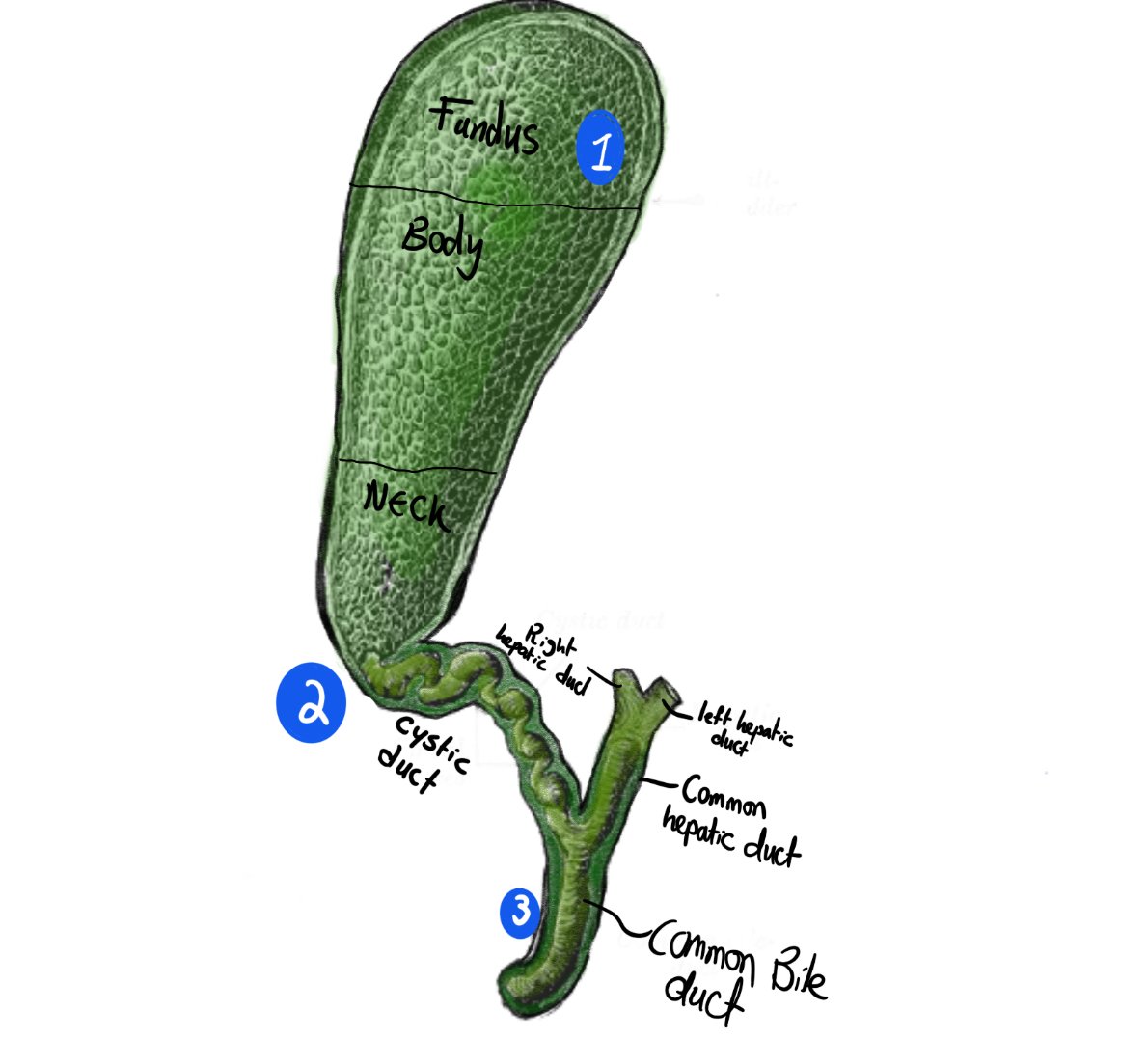

Gallbladder Anatomy

Capacity

The gallbladder has a storage capacity of 30-50 ml.

Location

- The gallbladder sits at the cystic plate inside the gallbladder fossa, right of the ligamentum teres.

- It is attached to the liver by loose fibro-areolar tissue.

- Uninflamed, it has a slate blue appearance through its peritoneum.

Structure

Pear shaped structure, consists of a fundus, body, and neck.

The neck has a mucosal fold called Hartmann's pouch, a common location for gallstones to lodge.

Cystic artery

It has a single cystic artery lying posteriorly to the cystic duct inside Calot's triangle (see Calot's triangle below).

Cystic duct

The cystic duct is 2-4cm, entering the common bile duct at an angle.

Anatomical relations of the gallbladder

The gallbladder is entirely surrounded by peritoneum, and is in direct relation to the visceral surface of the liver.

Relation |

Organs |

|---|---|

Anteriorly and superiorly |

Inferior edge of the liver |

Posteriorly |

Duodenum and transverse colon |

Inferiorly |

Remainder of the biliary tree and duodenum and part of the transverse colon. |

Adhesions with these surrounding structures are common after inflammation of the gallbladder.

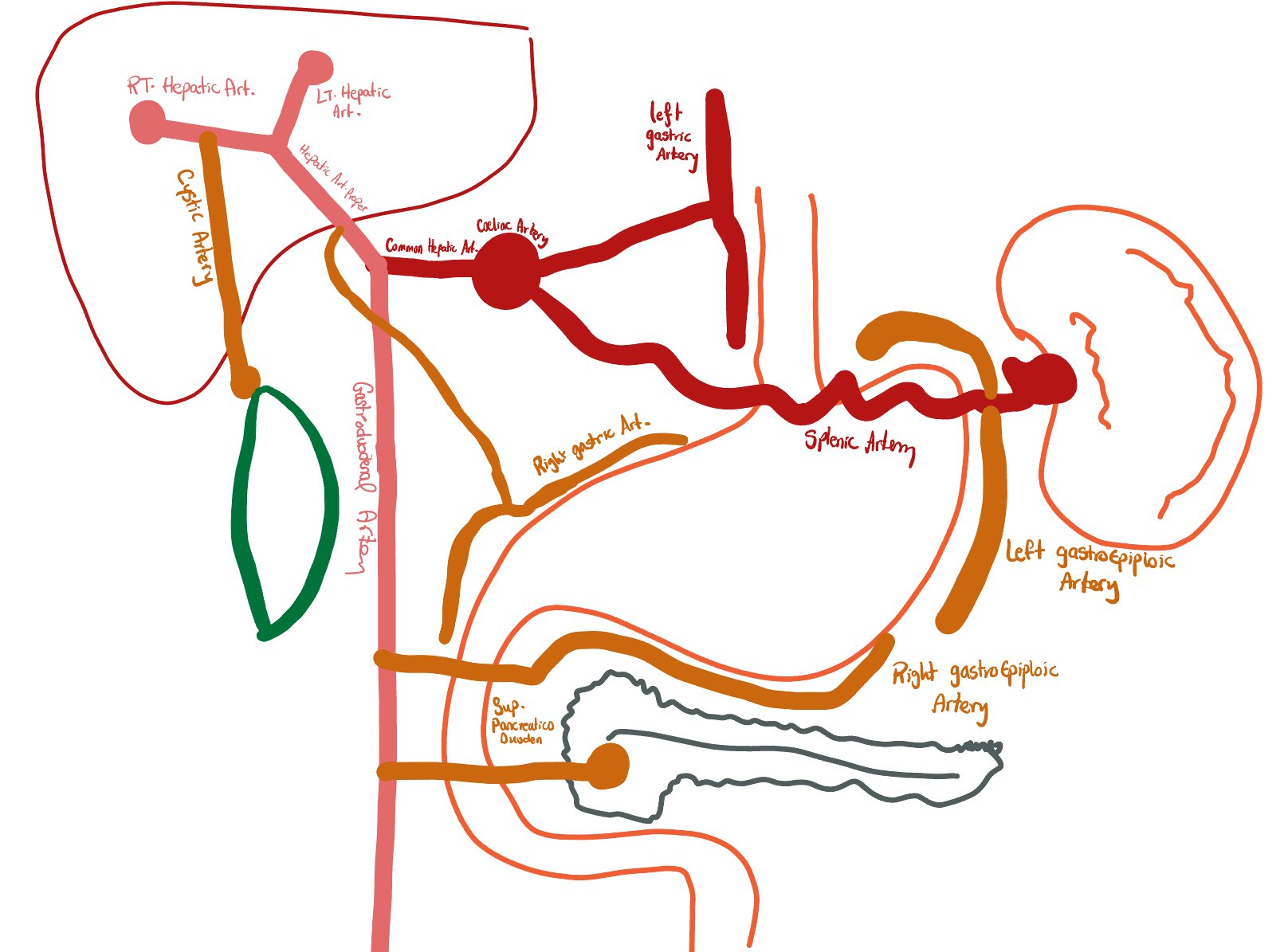

Blood supply of the gallbladder

Main blood supply

- The main blood supply is via the cystic artery, a branch of the right hepatic artery, which is a branch of the hepatic artery proper, which is a branch of the coeliac axis.

Secondary blood supply:

- The gall bladder gets a secondary blood supply from the cystic plate of the liver where it lies.

Summary of blood supply to the gallbladder

Abdominal Aorta

Coeliac axis

Hepatic Artery Proper

Right Hepatic Artery

cystic artery

Underground style map depicting route of the cystic artery

Nerve supply of the gallbladder

- Sensory supply: Coeliac plexus

- Sympathetic supply: Coeliac plexus

- Parasympathetic supply: Vagus nerve

Lymphatic drainage of the gallbladder

- A prominent lymph node is usually found overlying the cystic artery near its insertion in the gallbladder.

- This is often termed the sentinel node or Calot's node.

- 2 lymph node chains drain the gallbladder:

- Between the CBD and portal vein

- Between the hepatic artery and portal vein

- A lymphadenectomy for gallbladder malignancy should involve skeletonisation of the CBD, portal vein, and hepatic artery and removal of nodes above the duodenum.

Microscopic anatomy of the gallbladder

The gallbladder wall comprises:

- Serosa (visceral peritoneum): only covering the inferior free surfaces of the gallbladder.

- Muscular outer layer (non-striated muscle cells arranged in a circular, oblique, and longitudinal arrangement).

- Lamina propria.

- Mucosa (single-cell layer of cuboidal epithelium).

Anatomical triangles relating to the gallbladder

Anatomical variations

- Various studies looked into the different anatomical variations that can be encountered when performing a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

- Studies report around 30% of patients will have an anatomical variation, which means it is essential to know the variations.

- Vasculobiliary injuries are the major cause of morbidity in patients undergoing cholecystectomy; misinterpretation and anatomical variations are the most common factors that increase the risk of this.

- Images used below were noted from this study published in Annals of Medicine and Surgery:

Gallbladder variations

Normal gallbladder (at gallbladder fossa)

Normal gallbladder sitting in the gallbladder

Gall bladder diverticulum

Rare anomaly of a divericular outpouching from the gallbladder.

Intrahepatic gallbladder

- The intrahepatic gallbladder has its entire circumference surrounded by liver parenchyma.

- In some cases (see below), part of the gallbladder's fundus can stick out of the liver parenchyma.

Cystic duct variations

The Cystic duct can join the common hepatic ducts in different configurations:

Normal gallbladder sitting in the gallbladder

Length of cystic duct

- Normal is considered around 2-4 cm

Long cystic duct (over 4 cm)

- This can be advantageous as it allows easy manipulation of the duct and easy clipping of the duct.

- A long spiralling duct can be difficult to identify and increases risk of CHD injury.

Short cystic duct (less than 2 cm)

- A short duct can be difficult to manipulate, reduces access to Calot's triangle.

- It is also more difficult to clip.

Cystic duct's normal configuration:

- The cystic duct normally joins the common hepatic duct at a wide angle as shown in the image below

- This is the case in over 70% of patients

Angular (70%)

Cystic duct's variant configuration:

Parallel 20%

This variant involves a very long cystic duct running parallel to the common bile duct.

Spiral (10%)

This involves a long cystic duct that spirals around the common hepatic duct

Rarely the cystic duct can join the right hepatic duct directly

Cystic artery

THe normal setup of the cystic artery is an artery sitting posterior to the cystic duct (see image below)

Cystic artery variations

Cystic artery anterior to the cystic duct

If pulsation is not clear, this can be difficult to identify

Double cystic artery

Can cause bleeding if first artery identified and clipped but second artery not noted and inadvertently cut (due to not anticipating presence of a second artery).

Cystic artery originating from liver parenchyma

Cystic artery forming a caterpillar hump appearance

Biliary Tree Overview

Intrahepatic Drainage: From Hepatocytes to Hepatic Ducts

- Hepatocytes secrete bile into fine intracellular channels known as bile canaliculi.

- These canaliculi drain into the canals of Hering.

- These short transitional channels, lined by a combination of hepatocytes and biliary epithelial cells (cholangiocytes), then guide the bile into the interlobular bile ducts.

- These ducts, now fully lined by cholangiocytes that can modify bile, travel alongside branches of the portal vein and hepatic artery within the portal triads.

- This elaborate intrahepatic network culminates in the formation of the right hepatic duct (draining the right functional lobe) and the left hepatic duct (draining the left functional lobe).

- These two principal ducts then emerge from the liver at the porta hepatis.

Formation of the Major Extrahepatic Bile Ducts

- Just outside the liver, typically at the porta hepatic, the right and left hepatic ducts unite to form the common hepatic duct.

- This duct, usually a few centimeters in length, serves as the primary conduit for bile synthesized by and draining from the liver.

- The common hepatic duct then courses downwards and is soon joined by the cystic duct which carries bile to and from the gallbladder.

- The union of the common hepatic duct and the cystic duct marks the beginning of the common bile duct (CBD).

Diagram illustrating the gallbladder and biliary ducts

Summary of the formation of the CBD:

The common hepatic Duct

- The common hepatic duct is formed when the right and left hepatic ducts join together.

- It collects bile synthesised by liver for drainage.

- The right hepatic duct drains bile from the liver's right functional lobe, while the left hepatic duct drains bile from the liver's left functional lobe.

Common Bile Duct

The common hepatic duct joins with the cystic duct (from the gallbladder) to form the common bile duct.

Common Bile Duct

The common hepatic duct joins with the cystic duct (from the gallbladder) to form the common bile duct.

The Common Bile Duct (CBD)

Definition and Formation:

- A duct foirmed by the union of the common hepatic duct and the cystic duct.

- It's primary function is to channel bile—originating from both liver synthesis and gallbladder storage—into the duodenum to aid in digestion.

Anatomical Course and Relationships:

- Origin: The CBD commences at the confluence of the common hepatic duct and the cystic duct, a junction typically situated near the porta hepatis.

- Course: From its origin, the CBD descends, initially positioned within the free edge of the lesser omentum. Its path then takes it posterior to the first (superior) part of the duodenum. Subsequently, it continues its descent either embedded within the posterior aspect of the head of the pancreas or coursing through a groove in this glandular tissue.

- Termination: The CBD culminates by passing through the duodenal wall and emptying its contents into the lumen of the second (descending) part of the duodenum. This entry point is a shared opening with the main pancreatic duct at the hepatopancreatic ampulla (also known as the ampulla of Vater).

- The release of bile and pancreatic juice into the duodenum at this point is regulated by a smooth muscle valve called the sphincter of Oddi.

Dimensions:

- Normal Diameter: The typical diameter of a healthy common bile duct is up to 6 millimeters.

- It can be considered normal for the diameter to be slightly larger, potentially up to 8 millimeters, in elderly individuals or in patients who have undergone cholecystectomy, as the CBD may dilate to compensate for the loss of the gallbladder's storage capacity.

- Regulation of Bile Flow: The flow of bile into the intestine is not continuous but is regulated:

- The sphincter of Oddi, a sphincter surrounding the ampulla of Vater, controlling the timing and volume of bile (and pancreatic secretions) released into the duodenum.

- During periods of fasting, when digestion is not actively occurring, the sphincter of Oddi is usually contracted (closed). This closure increases pressure within the common bile duct, causing bile to back up through the cystic duct and be diverted into the gallbladder for concentration and storage. A smaller portion may still pass intermittently into the duodenum.

Diagram illustrating the configuration of distal bile ducts and pancreatic duct, highlighting sphincter distribution

Anatomical Relationship between the CBD and the Pancreas

- The common bile duct (CBD) maintains an intimate and clinically significant anatomical relationship with the head of the pancreas. The exact nature of this relationship can vary among individuals, with several common configurations observed:

- Partially covered posteriorly: The CBD runs in a groove on the posterior aspect of the pancreatic head (most common, approximately 50% of cases).

- Completely covered (intrapancreatic): The CBD is entirely tunnelled through the parenchyma of the pancreatic head (approximately 30% of cases).

- Completely uncovered: The CBD lies on the surface of the pancreas without being covered by pancreatic tissue (approximately 16.5% of cases).

- Rarely, the CBD may pass lateral to the pancreatic head.

Illustrations detailing the CBD's anatomical relationship with the pancreas

Bile Composition

Bile is a complex fluid produced by the liver, playing vital roles in digestion and waste excretion. Its main components include:

Cholesterol

Cholesterol: A lipid synthesized by the liver and excreted into bile. While essential for various bodily functions, its relative insolubility in the aqueous environment of bile means that an excess concentration, or an imbalance with solubilizing agents like bile salts and phospholipids, can lead to its precipitation and the formation of cholesterol gallstones.

Electrolytes

Electrolytes: Bile contains a variety of electrolytes, including sodium, potassium, calcium, chloride, and notably bicarbonate. Bicarbonate, actively secreted by cholangiocytes, contributes to the alkaline nature of bile, which helps neutralize stomach acid in the duodenum and optimize the pH for digestive enzyme activity.

Water

Water: Constituting the largest proportion of bile (typically 85-95%), water serves as the primary solvent for all other biliary components, facilitating their transport through the biliary tract and into the intestine.

Other Key Components

Beyond the above, bile is rich in:

- Bile salts: These are critical for fat digestion and absorption. Synthesized from cholesterol in hepatocytes and conjugated with amino acids (glycine or taurine) to form bile salts, they act as detergents, emulsifying dietary fats into smaller micelles. This greatly increases the surface area for pancreatic lipase to act upon.

- Phospholipids (mainly Lecithin): These work in conjunction with bile salts and cholesterol to form mixed micelles, aiding in the solubilization of cholesterol and contributing to fat emulsification.

- Conjugated Bilirubin: A yellow pigment that is a metabolic byproduct of heme breakdown (from red blood cells). The liver conjugates bilirubin to make it water-soluble for excretion into bile, giving bile its characteristic color and serving as a route for eliminating this waste product.

- Minor amounts of proteins and trace metals are also present.

Fasting State

During the fasting state (interdigestive periods), the sphincter of Oddi at the duodenal end of the common bile duct is typically contracted. This increased resistance diverts a significant portion of the continuously produced hepatic bile (approximately half or more) up through the cystic duct into the gallbladder. Here, bile is concentrated by water and electrolyte absorption and stored until needed. A smaller portion may still pass intermittently into the duodenum.

Post-Meal Release

Following the ingestion of a meal, particularly one containing fats and proteins, these nutrients entering the duodenum trigger the release of the hormone cholecystokinin (CCK) from enteroendocrine cells in the duodenal mucosa.

CCK then acts systemically, primarily stimulating two coordinated events:

- contraction of the gallbladder and simultaneous relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi.

- This concerted action propels the concentrated, stored bile from the gallbladder through the cystic and common bile ducts, and allows both stored and freshly produced hepatic bile to flow freely into the duodenum to participate in digestion.

Bile Function in Digestion and Excretion

Fat Emulsification

fat emulsification: Bile acids and salts, along with phospholipids, act as powerful detergents in the aqueous environment of the small intestine. They break down large dietary fat globules into microscopic droplets, a process called emulsification. This dramatically increases the surface area of lipids available for enzymatic action by pancreatic lipase, thereby greatly enhancing the efficiency of fat digestion.

Absorption of Digested Fats

Bile acids also form micelles with the products of fat digestion (fatty acids, monoglycerides, cholesterol, and fat-soluble vitamins). These micelles are tiny water-soluble complexes that transport these poorly soluble lipids through the aqueous layer of the intestine to the surface of enterocytes (intestinal absorptive cells), facilitating their absorption into the body.

Enterohepatic Circulation

The body efficiently conserves bile acids through the enterohepatic circulation. After facilitating fat digestion and absorption, the majority (around 95%) of bile acids are actively reabsorbed in the>terminal ileum (the final section of the small intestine). From here, they enter the portal venous blood and are transported back to the liver. Hepatocytes then efficiently extract these bile acids from the portal blood, reconjugate them if necessary, and re-secrete them into bile. This recycling pathway, which may occur several times per meal, ensures a sufficient pool of bile acids for digestion while minimizing the need for de novo synthesis.

Waste Product Excretion

Bile serves as an important vehicle for the excretion of various endogenous waste products and xenobiotics (foreign compounds) from the body. Key substances eliminated via bile include conjugated bilirubin (a breakdown product of hemoglobin), excess cholesterol (which cannot be broken down by the body), and certain drug metabolites. These substances are transported into the intestine with bile and are ultimately eliminated in the feces.

Clinical View Overview

Content for "Clinical View" main tab. Please select a sub-topic.

Clinical Placeholder Section 1

More detailed content about clinical aspects of the gallbladder...

Clinical Placeholder Section 2

Further clinical discussions and case studies...

Gallstone disease

Gallstones are very common affecting around 1 in 12 patients. The presence of gallstones can lead to multiple complications which we will dive into below.

Introduction

- Gallstone disease refers to any symptoms or diseases caused by the presence of gallstones in the biliary system

- Gallstones are hard pebble like material, that develop in the gallbladder.

- Gallstone disease can have a wide variety of presentations and this varies according to the location of the stones in the biliary tract.

Aetiology of stone formation

| Stone type | Composition | Prevalence | Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol | High cholesterol, low electrolytes | 80% | 5Fs (see below) |

| Black Pigment | High calcium and bilirubin | 15% | Altered bilirubin metabolism |

| Brown | Calcium and fatty acids | 5% | Chronic biliary tract infections |

Pathophysiology of gallstones disease

How do Cholesterol stones form?

Cholesterol Supersaturation

Excess cholesterol in bile leads to supersaturation, the first step in stone formation.

Nucleation

Crystallisation promoting factors, such as glycoproteins, facilitate the formation of cholesterol crystals.

Stone Growth

Reduced gallbladder motility allows crystals to aggregate and form larger stones over time.

Black Pigment Stones

Composition

Black pigment stones are primarily composed of calcium bilirubinate, resulting from increased bilirubin in bile.

Haemolytic Disorders

Conditions such as sickle cell disease and spherocytosis increase the risk of black pigment stone formation due to chronic haemolysis.

Cirrhosis

Liver cirrhosis is associated with an increased risk of black pigment stones due to altered bilirubin metabolism.

Bile Salt Loss

Conditions affecting the terminal ileum can lead to bile salt loss, increasing bilirubin reabsorption and stone risk.

Brown Stones:

Biliary Infection

Chronic biliary infections, often due to parasites or bacteria, create an environment conducive to brown stone formation.

Bile Stasis

Reduced bile flow, often due to biliary strictures or previous surgeries, promotes bacterial growth and stone formation.

Stone Composition

Brown stones are composed of calcium salts of fatty acids, resulting from bacterial action on bile components.

Risk factors

The risk factors for formation of cholesterol stones can be remembered by the mnemonic 5Fs.

Female

Women are more prone to gallbladder disease, especially during childbearing years.

Fat

Obesity is a significant risk factor for developing gallstones.

Excess body weight increases cholesterol production and secretion into bile. Elevated leptin levels in obesity further promote stone formation.

Paradoxically, rapid weight loss can increase risk due to mobilisation of cholesterol stores and reduced gallbladder motility.

Fair

Caucasians have a higher prevalence of gallbladder disease.

Specific gene mutations affecting cholesterol metabolism and bile salt composition have been identified as risk factors.

Fertile

Women under 40, especially those who have been pregnant, are at increased risk.

Hormonal changes during pregnancy alter bile composition and reduce gallbladder motility, increasing stone risk.

40 year old

The avarage age of presentation with gallstones is 40 years old,

Clinical Presentation

Stones in the gallbladder

Asymptomatic Gallstones- Some patients may be completely asymptomatic, and the stones will be found incidentally on imaging requested for other indications.

- Many asymptomatic gallstones remain stable for years without causing complications or requiring treatment.

- Patients can present with transient episodes of RUQ pain.

- Pain is triggered by a meal that contains fat.

- The gallbladder's function is to store bile. It contracts to push the bile into the biliary tree in response to cholecystokinin, which is produced in response to ingestion of fat.

- Pain is thought to be due to the gallbladder contracting secondary to the hormone cholecystokinin in response to ingestion of fat.

Stones in the gallbladder neck / Cystic Duct

Cholecystitis- The presence of a stone in the gallbladder neck or cystic duct causes stasis of bile in the gallbladder.

- Stasis of bile in the gallbladder can lead to infections in the gallbladder (cholecystitis).

Stones in the common bile duct (choledocholithiasis)

Ascending cholangitis- Stones in the common bile duct cause an obstruction that prevents bile drainage.

- This causes jaundice and stasis of bile, which can lead to infection (cholangitis).

Stones blocking the pancreatic duct

Pancreatitis- Gallstones are a very common cause of acute pancreatitis.

- More on this in the pancreatitis notes.

Diagram depicting the location of stones in: 1) Biliary colic / asymptomatic stones, 2) Cholecystitis, 3) Ascending cholangitis.

Summary of stone location vs presentation

| Stone Location | Clinical Presentation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Gallbladder | Biliary colic | Self limiting episodes of RUQ pain. |

| Gallbladder neck or Cystic duct | Biliary colic, Acute cholecystitis | RUQ pain, Murphy's sign, fevers, raised inflammatory markers. |

| Common bile duct | Obstructive jaundice, Cholangitis | Jaundice, fever, abdominal pain, raised billirubin |

| Ampulla of Vater | Pancreatitis | Epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, raised amylase. |

Diseases associated with gallstones

Biliary Colic

Definition

Biliary colic is a symptom, not a disease, characterised by right upper quadrant or epigastric pain due to contraction of a gallbladder against stones.

Trigger

Often precipitated by fatty meals, which stimulate cholecystokinin release and gallbladder contraction.

Duration

Pain typically lasts for several hours, distinguishing it from other abdominal pain syndromes.

Associated Symptoms

May be accompanied by nausea and vomiting, but notably without fever.

Acute Cholecystitis:

Initial Obstruction

A gallstone becomes lodged in the gallbladder neck, gallbladder neck or Cystic duct obstructing bile flow from the gallbladder.

Inflammation

Trapped bile irritates the gallbladder wall, leading to chemical inflammation.

Bacterial Infection

Stasis of bile creates an ideal environment for bacterial growth, often E. coli, leading to secondary infection.

Progression

Without treatment, inflammation can progress to empyema, gangrene, or perforation.

Clinical Features of Acute Cholecystitis

Pain Characteristics

Persistent right upper quadrant pain, more severe and prolonged than biliary colic. May radiate to the right shoulder or back.

Systemic Symptoms

Fever, chills, and general malaise indicate systemic inflammation. Nausea and vomiting are common.

Physical Examination

- Tenderness in the right upper quadrant, often with guarding. Murphy's sign is typically positive, indicating gallbladder inflammation.

- Murphy's sign:

- Examiner places fingers gently on the right upper quadrant, just below the costal margin.

- Patient is asked to take a deep breath, causing the gallbladder to descend and contact the examiner's fingers.

- A positive Murphy's sign occurs when the patient abruptly halts inspiration due to pain.

Important differentials to consider when assessing Right Upper Quadrant Pain

Gastrointestinal

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Hepatic flexure tumour

- Irritable bowel syndrome

Hepatobiliary

- Acute hepatitis

- Liver abscess

- Budd-Chiari syndrome

Other Systems

- Renal colic

- Right lower lobe pneumonia

- Myocardial infarction (rare)

Investigations for Suspected Gallbladder Disease

Blood Tests

- Rise in inflammatory markers is seen (Raised WCC and raised CRP) due to infection.

- liver function tests

- A rise in ALP and GGT due to inflammation damaging cells in the biliary tract.

- AST and ALT can be mildly raised in uncomplicated cholecystitis, but the rise is to a much lesser extend.

- Bilirubin should be normal in cholecystitis as there is no biliary obstruction.

- Amylase:

- Checked to rule out acute pancreatitis, which can present similarly. This should be normal in uncomplicated cholecystitis.

- Troponin: a myocardial infarction can be an important differential to rule out in upper abdominal disease.

- Chest xray: to rule out right lower lobe pneumonia as a cause for RUQ pain.

Imaging

Abdominal ultrasound is the gold standard for initial imaging, offering high sensitivity for gallstones and signs of inflammation.

- Findings on Ultrasound in cholecsytitis:

- Appear as echogenic foci with acoustic shadowing, often mobile with patient positioning.

- Gallbladder wall >3mm suggests inflammation, characteristic of acute cholecystitis.

- Pericholecystic Fluid

- Indicates more severe inflammation or potential perforation.

- USS should show no evidence of CBD obstruction

- The CBD should be of normal caliber

image depicting an ultrasound of a gallbladder with gallstones. Note tha accousting shadowing formed the stone.

Complications of cholecystitis

Empyema

Accumulation of pus in the gallbladder.

Perforation

Gallbladder wall rupture leading to billiary peritonitis, leading to septic shock.

Mirizzi's Syndrome

Rare complication where a stone in the cystic duct compresses the common hepatic duct.

Gallbladder Cancer

Long-standing inflammation increases the risk of gallbladder malignancy.

Cholecystoduodenal fistula:

Multiple severe episodes of cholecsytitis can lead to a fistula to form between the gallbladder and the duodenum.

obstruction of the GI tract due to gallstones:

This is a rare complication of gallstone disease.

How does it occur?

The obvious way a stone can reach the GI tract from the gallbladder would be through the billiary tree. You may be asking yourself "How would a stone that could pass through a CBD that has a diameter less than 7mm obstruct the small bowel?

The answer is it can't!. Stones that cause obstruction reach the GI tract through a different route.

The steps for gallstone ileus to happen are typically as listed below:

Recurrent inflammation of the gallbladder.

Recurrent episodes of cholecystitis predispose patients to formation of adhesion and fistulae with the duodenum

Fistula formation

IF recurrent episodes of cholecystitis are not treated surgically, they can lead to formation of a cholecystoduodenal fistulae.

Given bile is excreted from the billiary system into the duodenum anyway, those fistulae remain asymptomatic.

On a CT scan, you may no pneumobillia (air in the billiary tract) and loss of wall sign between gallbladder and duodenum.

Obstruction of the GI tract:

This fistula creates a wide connection between the gallbladder and the bowel. A large stone in the gallbladder can drop through this large connection reaching the GI tract.

- Bouveret Syndrome: A condition characterised by large gallstones obstruct the duodenum or gallbladder causing gastric outlet obstruction.

- Gallstone ileus: A stone can pass through the duodenum and jejunum easily due to their wider lumen, but may get stuck in the ileum as it typically has a narrower lumen, leading to bowel obstructiion AKA gallstone ileus.

Management of Acute Cholecystitis

Initial Management

IV fluids, analgesia, and nil by mouth. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are initiated to cover common biliary pathogens.

Antibiotic Choice

Typically a broad-spectrum antibiotic Tazocin or Co-Amoxiclav can provide cover against gram negative and anaerobes ((use your local guidelines!!)).

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (see surgeon's view)

- Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy (within 72 hours) is preferred if the patient is fit for surgery.

- This is referred to as a "Hot laparoscopic Cholecystectomy”.

- Most guidance recommends not to attempt a lap chole after 72 hours from symptoms starting, as adhesions would have formed by this point, making the operation difficult and increasing risk of complications such as ductal injuries or bleeding.

- An operation is usually delayed for about 6 weeks as long as the patient has responded to antibiotic therapy.

Percutaneous cholecystostomy

A tube inserted into the gallbladder by interventional radiologists.

- This may be considered in high-risk patients unfit for immediate surgery to drain sepsis and control the source of infection.

- This tube is inserted into the gallbladder and is kept in place for a number of weeks (4-6) ((check local guidelines)).

- The tube is kept in until a tract forms between the skin and the gallbladder.

- This prevents the defect caused by the tube insertion from causing bile to leak into the abdomen.

- If a bile leak happens after tube removal, it will leak through the skin and a small drain bag can be attached to catch this until it resolves.

- The tube is sometimes left until the date a cholecystectomy is planned or kept indefinitely in patients with recurrent biliary sepsis who are not fit for an operation.

Ascending Cholangitis:

Definition

Ascending cholangitis is a severe infection of the biliary system, typically caused by bacterial colonisation of an obstructed bile duct.

Charcot's Triad

The classic presentation includes right upper quadrant pain, fever, and jaundice, though not all symptoms may be present.

Aetiology

Most commonly the obstruction is caused by gallstones, but can also result from strictures, tumours, or iatrogenic causes like ERCP.

Urgency

Considered a medical emergency due to the risk of rapid progression to sepsis and multi-organ failure.

Diagnosis of ascending cholangitis

Bloods

- WCC and CRP are raised due to presence of an infection.

- LFTs:

- ALP and GGT are raised.

- Bilirubin is raised.

- Small rise in ALT and AST can be seen (less in comparison to ALP and GGT).

Imaging

Ultrasound:

- Can show a widened CBD (over 7mm).

- Can confirm presence of stones or gallbladder inflammation

MRCP (MR cholangiopancreatography):

- The most sensitive radiological investigation to assess presence of CBD stones/ assess the cause of CBD obstruction causing this inflammation.

ERCP: A Crucial Tool in management of biliary disease

What is an ERCP

- ERCP stands for endoscopic-retrograde-cholangiopancreatography-

- Can be used as a diagnostic tool to assess the cause of biliary obstruction, and to obtain brushings (biopsies) of any abnormalities in the biliary tract.

- Can also be used to treat biliary obstruction causing ascending cholangitis.

Description

A procedure combining endoscopic and fluoroscopic techniques.

Endoscopy

A side-viewing endoscope passed through the mouth into the duodenum (D2).

Cannulation

The papilla is cannulated, and contrast is injected to visualise the biliary tree using X-ray.

Endoscopy

A side-viewing endoscope passed through the mouth into the duodenum (D2).

Cannulation

The papilla is cannulated, and contrast is injected to visualise the biliary tree using X-ray.

Sphincterotomy

If necessary, the sphincter of Oddi is cut to allow better access and stone removal.

Stone Extraction

Stones are removed using baskets or balloons under fluoroscopic guidance.

Biopsies

Brushings can be taken from any abnormal appearing tissue.

Post-ERCP Complications

The most common complication, occurring in 3-5% of cases. Risk factors include young age, female gender, and difficult cannulation.

There is an argument that younger females should not have an ERCP as first-line for biliary tract decompression due to the significantly increased risk of pancreatitis, and that they should be considered for CBD exploration instead.

Bleeding

Can occur after sphincterotomy, especially in patients with coagulopathy. Usually self-limiting but may require endoscopic intervention.

Perforation

Rare but serious complication. Can occur due to guidewire manipulation or excessive sphincterotomy. May require surgical intervention.

Cholangitis

Can occur if biliary drainage is incomplete. Prophylactic antibiotics are often given to high-risk patients.

A septic shower phenomenon can be seen in patients post decompression of biliary should be tract obstruction, especially in patients with significant ongoing cholangitis.

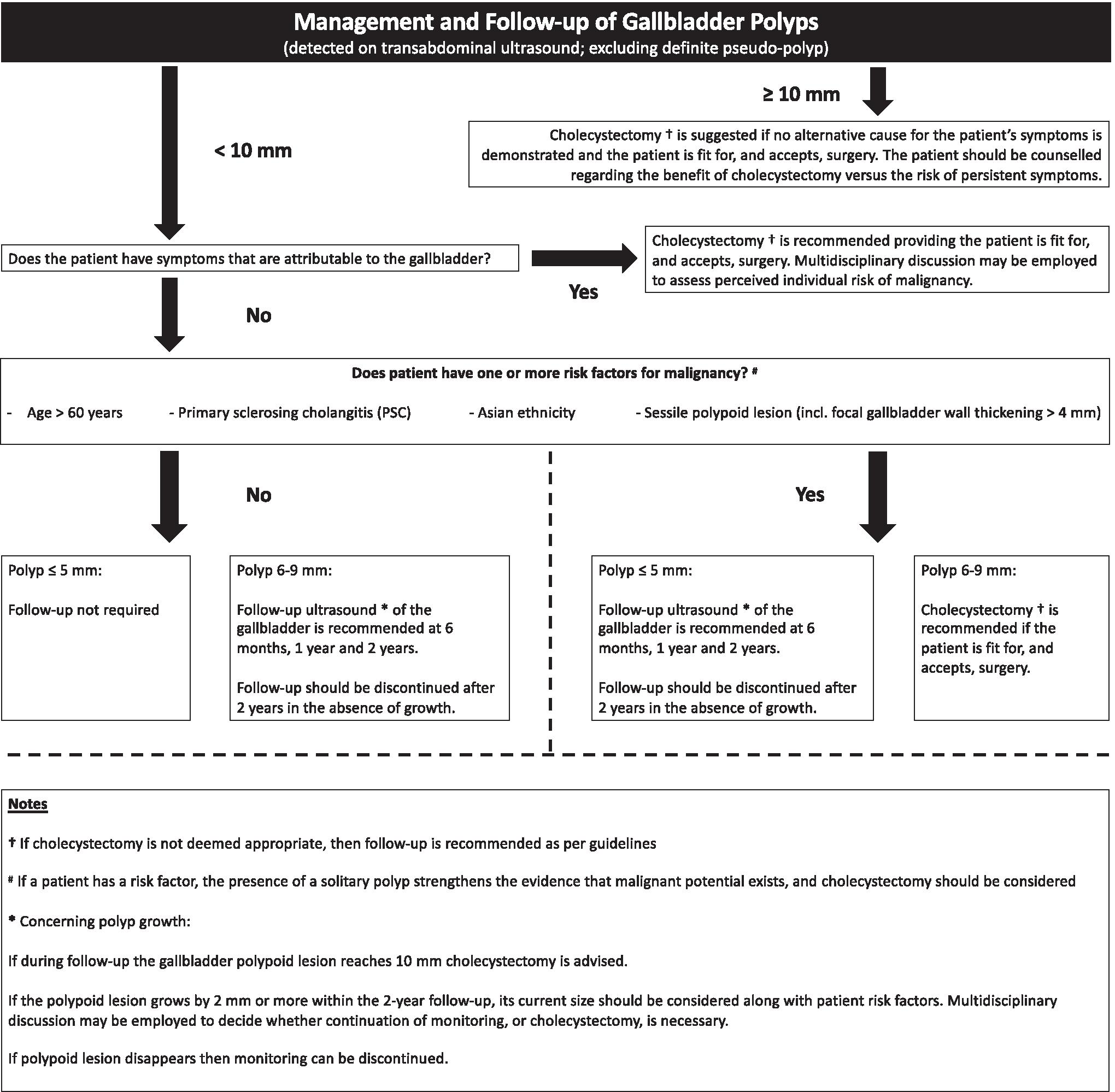

Gallbladder Polyps (GPs)

what is a gallbladder polyp

- polypoid lesions that project from the gallbladder wall into the gallbladder interior are called gallbladder polyps (GPs).

- Polyps are found incidentally in around 5% of all abdominal ultrasounds

- The majority of GPs are benign but some may be cancerous. Cancers of the gallbladder generally have very poor prognoses, which means it is important to differentiate benign and malignant polyps.

Diagram showing classification of gallbladder polyps according to histology.

Presentation of gallbladder poylps:

- The majority of patients with Gallbladder polyps are completely asymptomatic. The polyps are incidentally noted on ultrasound

- The difficulty is the malignant potential of polyps cannot be assessed on imaging.

Mangement of gallbladder polyps:

The management of gallbladder polyps in the UK is based on joint guidelines published by the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR), European Association for Endoscopic Surgery and other Interventional Techniques (EAES), International Society of Digestive Surgery—European Federation (EFISDS) and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE)

Flow chart of the guideline

Other diseases of the gallbladder (including carcinoma)

Adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder

- it is a chronic benign condition of the gallbladder wall.

- The consition is characterised by epithelial proliferation with muscular atrophy and mural diverticulae (Rokitasnky-Ashchoff sinuses).

- Those changes can be seen on US, CT and MRI.

- The presence of the sinuses differentiate adenomyomatosis from other cause of gallbladder wall thickening such as cholecystitis or gallbladder malignancy.

- Adenomyomatosis can cause ongoing chronic pain (similar to pain from biliary colic).

- The main treatment to this is laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Porelain gallbladder

- A rare condition characterised by widespread calcification of the gallbladder wall.

- This calcification can be seen on imaging such as CT or abdominal films.

- There is an increased risk of gallbladder carcinoma with porcelain gallbladder.

Gallbladder carcinoma

- A rare malignancy accounting to almost 50% of all biliary tract malignancies.

- Most tumours are adenocarcinomas, with squamous, adenosquamous and neuroendocrine tumours being less common.

- Early symptoms may be similar to biliary colic or cholecystitis.

- Gallbladder carcinoma presentations vary from incidentally detected neoplasms in gallbladders removed for other indications to full blown metastatic cancer with distant mets.

Biliary disease: Surgery view

The primary treatment for gallstone disease is a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This aims to relieve symptoms of biliary colic and to reduce risk of complications of gallstones including cholecystitis, ascending cholangitis and pancreatitis.

Should everyone with gallstones get a lap chole?

NICE guideline [CG188] discusses the management of gall stones. It recommends the following

- Reassure people with asymptomatic gallbladder stones found in a normal gallbladder and normal biliary tree that they do not need treatment unless they develop symptoms.

- asymptomatic gallstones are defined as stones found incidentally on imaging which was requested for an indication not relating to gallstones.

- Offer a laparoscopic cholecystectomy to patients diagnosed with symptomatic gallbladder stones.

The decision to operate should be made a “shared decision” between the patient and the medical team. This decision should be made after careful consideration of risks vs benefits.

What does a laparoscopic cholecystectomy involve

Day case:

- NICE recommends lap choles to be offered as a day case to fit and well patients.

- Patients with significant comorbidities or social issues can be offered overnight stay.

- Patients requiring drain insertion or who have had significant intraoperative complications will require a prolonged stay.

Pre-operative Preparation and Patient Selection

- Medical History and Imaging: Detailed patient history, focusing on symptoms and previous abdominal surgeries. Ultrasound is essential for confirming gallstones.

- Risk Assessment: Evaluate for risk factors like acute cholecystitis, gallstone pancreatitis, and choledocholithiasis. Consider MRCP or EUS if bile duct stones are suspected.

Informed consent

Discuss risks and benefits of undertaking a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. It is pertinent to ensure the patient is aware of the intervention and its alternative (conservative management).

Benefits of the operation:

- Reduction in pain associated with biliary colic

- Reduction in risk of complications associated with gallstones (cholecystitis, ascending cholangitis and pancreatitis.

Risks of the operation

Bleeding

Could happen due to any of the following:

- Injury to hepatic vessels.

- bleeding from the gallbladder fossa.

- bleeding from the clipped cystic artery.

Infection

The gallbladder contains bile. Any instrumentation involving it means the operation is inherently non-sterile.

The infection can be to any of the following:

- skin infection

- deeper wound infection

- collection post op

Injury to bowel, major vessels:

- This can be recognised during the procedure. Rarely it is missed intra-operatively and recognised post-op when patients become unwell.

- Can happen due to a multitude of reasons, but commonest is due to port insertion or division of adhesions between colon/bowel and gallbladder after severe cholecystitis episodes.

Bile leak

- Different risks quoted in literature, author uses a figure of less than 1 in 20 in his consent forms. This risk is probably on the higher end.

- Risk increased if there is blockage in the CBD due to retained stones. This is because bile can’t drain through the CBD and will create pressure on the clipped Cystic duct.

- This complication requires a return to theatre for washout, drain insertion and repair of the leak.

Ductal injury:

- This is a major complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomies.

- It is associated with very major morbidity and mortality.

- Management of this is through biliary reconstruction done by hepaticopancreaticobiliary specialists.

Types of ductal injuries

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| A | Cystic duct leak or leak from small ducts in the liver bed |

| B | Occlusion of an aberrant right hepatic duct |

| C | Transection without ligation of an aberrant right hepatic duct |

| D | Lateral injury to a major bile duct |

| E | Circumferential injury to a major bile duct: |

| E1 | Transection or stricture >2 cm from the hilum |

| E2 | Transection or stricture <2 cm from the hilum |

| E3 | Transection at the level of the bifurcation, without loss of contact between the left and right hepatic duct |

| E4 | Transection at the level of the bifurcation with loss of communication between the left and right hepatic duct |

| E5 | An injury of a right segmental duct combined with an E3 or E4 injury |

Port-site hernia:

- increased risk in patients who heavy lift early post-op.

- patients to be advised not to heavy lift for at least 4 weeks post-op. (I tell patients nothing heavier than a full tea kettle for 4 weeks).

Post cholecystectomy syndrome:

Post-cholecystectomy syndrome (PCS) is a poorly understood condition characterised by ongoing pain post cholecystectomy. It is thought to be caused by bile leaking into areas such as the stomach, or by gallstones being left in the bile ducts. In most cases symptoms are mild and short-lived, but they can persist for many months requiring prolonged use of pain relief.

Risks of general Anaethetic:

- Usually discussed by anaesthetist pre-op.

Performing a laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

Equipment List

- Primary Instruments: High-definition laparoscopic camera, trocars (2x 10mm 2x5mm), laparoscopic grasper, scissors, hook electrocautery, and clip applier.

- Specialized Instruments: Intraoperative cholangiogram equipment, ultrasonic dissectors, or advanced energy devices if needed.

Port setup:

| Label | position | size | use of port | notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | infraumbilical port | 10mm | camera | inserted using modified Hasson Cutdown technique. |

| T2 | Right lateral subcostal (right axillary line) | 5mm | grasper for retraction of gallbladder superiorly to allow disection of Calot’s | inserted using a sharp trocar under direct vision |

| T3 | Right subcostal midclavicular port | 5mm | For the left hand instrument | ensure triangulation with epigastric and infraumbilical port |

| T4 | epigastric port | 5-10mm | for the right hand instrument | useful if 10mm, allows use of camera in the port to visualise retrieval of gall bladder in bag from umbilical port. |

A diagram depicting the port set up for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Positioning of surgeon/patient

Patient position

Patient will be positioned supine, reverse Trendelenberg and right side up will be useful during the operation to move small bowel away from the gallbladder for ease of operating.

Surgeon’s position

The operating surgeon will be to the patient's left, as well as the camera operator. A third surgeon may be on the patient's right for retraction.

Pro-tip:

- During a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, retraction is relatively passive since significant repositioning of the gallbladder is usually unnecessary during the dissection of Calot’s triangle. A laparoscopic grasper can be used to retract the gallbladder.

- To free the camera operator’s hand, two towel clips can secure the gallbladder retractor, eliminating the need for the first assistant to provide passive retraction, which can be effectively replaced by towel clips.

- Later, during the dissection of the gallbladder off the liver bed, active retraction should be utilised to help this process.

Exploration:

- Assess the abdominal content for any concurrent pathology.

Adhesiolysis:

- Carefully perform adhesiolysis using hook diathermy.

- Adhesions can be fairly extensive with duodenum, colon and or omentum in patients who have had severe cholecystitis previously.

- The aim of this dissection is to remove any adhesions to expose Calot’s triangle.

The dissection should remain about Rouviere’s sulcus

- This is a 2-5cm fissure between the right lobe and caudate provess of the liver.

- Appearance: Usually appears as a deep groove that's open at the medial end

- Significance: The cystic duct and artery are located above the sulcus, while the common bile duct is below it.

- Remaining about Rouvier’s sulcus ensures you reduce risk of CBD injury.

- Prevalence: Present in 82% of livers

Reliability: A relatively constant anatomical structure that can be reliably identified in most patients

Diagram depicting the position of Rouvier's sulcus in relation to disected cystic duct and artery

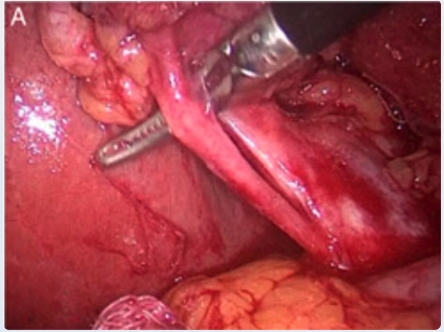

Achieving the critical view of safety

- The Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) have introduced a programme to reduce the rate of bile duct injuries.

- This programme aimed to reduce the number of CBD injuries which can be life altering leading to significant morbidity and cost.

- The critical view of safety is a method introduced as part of this programme.

The Critical view of Safety (CVS):

Three criteria are needed to achieve the CVS:

The hepatocystic triangle needs to be cleared of fat and fibrous tissue.

The hepatocystic triangle is defined as the triangle formed by the cystic duct, the common hepatic duct, and inferior edge of the liver.

The common bile duct and common hepatic duct do not have to be exposed.

gamma hepatocystic triangle image

The lower one third of the gallbladder is separated from the liver to expose the cystic plate.

The cystic plate is also known as the liver bed of the gallbladder and lies in the gallbladder fossa.

Two and only 2 structures should be seen entering the gall bladder

That pertains to the cystic artery and cystic duct.

Image showing the critical view of safety. Note the lower third of the gallbladder is off the cystic plate, note the hepatocystic triangle is cleared off fat and only 2 structures entering the gallbladder (cystic duct and cystic artery).

Image showing the critical view of safety. Note the lower third of the gallbladder is off the cystic plate, note the hepatocystic triangle is cleared off fat and only 2 structures entering the gallbladder (cystic duct and cystic artery).

Management of the cystic duct and artery

Dividing the cystic artery:

The cystic artery is clipped (2 clips proximally and 1 clip distally). It is then divided using lap scissors.

- It’s crucial to clip and cut the cystic artery before dividing the cystic duct.

- The cystic artery is a delicate and weak structure that is susceptible to tearing (avulsion) if it is pulled or subjected to traction after being divided.

- If the cystic duct is divided first, any manipulation or pulling of the gallbladder to access the cystic artery can cause the artery to avulse. This can lead to uncontrolled bleeding and complicate the surgery.

- By securing the cystic artery with clips and cutting it before addressing the cystic duct, you minimise the risk of avulsion because the artery is dealt with while it’s still intact and stable, reducing the need for additional manipulation that could cause damage.

Diagram depicting the method to clipping and dividing the cystic artery.

Dividing the Cystic Duct:

- The cystic duct is then clipped and cut in a similar fashion.

Diagram depicting the method to clipping and dividing the Cystic duct.

Gallbladder Dissection from Liver Bed:

Use a combination of blunt dissection and electrocautery, starting at the fundus and moving towards the neck.

It’s critical to dissect along the correct anatomical plane between the gallbladder and the liver to avoid complications:

Avoid Dissecting Too Deep into the Liver:

- Risks: Cutting too deeply into the liver tissue can cause significant bleeding from the liver parenchyma. Additionally, it may lead to leakage of bile from the small bile ducts within the liver (bile canaliculi) into the surgical field.

- Consequences: Excessive bleeding can obscure the surgical field, making the procedure more challenging and increasing the risk of injury to other structures. Bile leakage can lead to bile collections or bilomas, which may cause inflammation or infection postoperatively.

Avoid Dissecting Too Close to the Gallbladder:

- Risks: Dissecting too close to the gallbladder wall increases the chance of perforating it.

- Consequences:

- Bile Leakage: Perforation allows bile to spill into the abdominal cavity, contaminating the surgical field and increasing the risk of peritonitis or postoperative infections.

- Spillage of Gallstones: Gallstones may escape into the abdomen if the gallbladder is perforated. Should this happen, it’s imperative to meticulously search for and remove any spilled stones during the surgery.

- Potential Complications if Stones Are Missed:

- Formation of intra-abdominal abscesses around the retained stones.

- Development of adhesions or fistulas.

- The patient may require additional surgical interventions to address these complications, such as abscess drainage or even re-operation to remove the retained stones.

Bail-out procedures in difficult laparoscopic Cholecystectomies:

A laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be particularly challenging in patients who have experienced multiple episodes of cholecystitis. Recurrent inflammation leads to adhesions and fibrosis, complicating the surgical field. In such cases, accurately delineating the biliary anatomy becomes difficult, increasing the risk of ductal injuries.

If you are unable to achieve the critical view of safety due to excessive adhesions and fibrosis, it is crucial to recognize this issue and stop before causing a ductal injury. In these circumstances, employing a bail-out technique is advisable.

Bail-Out Techniques in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

Subtotal Cholecystectomy

Principle: “The best way to avoid a ductal injury is to not cut any ducts.”

- If you are uncertain about the identity of a duct, avoid transecting it.

- A subtotal cholecystectomy involves removing most of the gallbladder body while leaving a small cuff of the fundus. This approach minimizes dissection in the hepatocystic triangle and reduces the risk of ductal injuries.

- The remaining gallbladder fundus should be dissected off the liver bed and securely closed.

- Closure can be achieved using an endoloop or endoscopic suturing techniques.

- This is an effective operation that removes the majority of the gallbladder, reducing the risk of future stone formation while avoiding injury to the bile ducts.

Conversion to Open Surgery

- Converting to an open cholecystectomy can sometimes improve the handling of the gallbladder and facilitate safer dissection.

- However, many laparoscopic surgeons prefer the enhanced visualization provided by laparoscopy compared to the top-down view in open surgery. Therefore, conversion is not always the optimal solution in a difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Cholecystostomy and Closure

- If you are not confident in safely performing a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, it is prudent not to proceed.

- Patients generally prefer a conservative approach—such as drainage of sepsis via a cholecystostomy and subsequent closure—over the risk of a common bile duct (CBD) injury. A CBD injury may necessitate biliary reconstruction and can lead to infections, strictures, and increased mortality risk.

- There is no shame in aborting the procedure and referring the patient to a specialist if the critical view of safety cannot be safely achieved.